作者:Gaia Tisselli / 中興大學國政所國際交換生

翻譯:李燁、陳宛郁

本文詳細探討巴基斯坦境內恐怖主義的起源,以及巴基斯坦政府所面臨的困境。作者指出,雖然宗教因素是弱化政府治理與強化聖戰組織的主因,但背後的起源仍應歸咎於政治操弄的結果。而 1970 年代以降的阿富汗戰爭,成為聖戰士組織勢力逐漸茁壯與獨立的原因,更為巴基斯坦軍方和恐怖主義組織之間建立起深厚的淵源,導致一個獨立建國後原本一心嚮往邁向民主的國家,陷入自殺攻擊與教派仇殺的陰霾之中。

1. Defining terrorism 如何定義恐怖主義

There has always been a lot of contradiction in defining terrorism on the international scene, and many definitions have been given, but, as Bruce Hoffman, one of the world’s leading experts on terrorism argues in his book Inside Terrorism, first of all is necessary to distinguish it from what it is not, for example to mark a difference within terrorism and a guerrilla attack, or regular criminals, since both use violence to attain a specific purpose. Nonetheless, the medium utilized to get to the point can be the same (namely, violence), but the reasons for it are clearly not: as for guerrilla, “is taken to refer to a numerically larger group of armed individuals, who operate as a military unit, attack enemy military forces, and seize and hold territory (even if only ephemerally during daylight hours), while also exercising some form of sovereignty or control over a defined geographical area and its population. Terrorists, however, do not function in the open as armed units, generally do not attempt to seize or hold territory, deliberately avoid engaging enemy military forces in combat and rarely exercise any direct control or sovereignty either over territory or population.“ As for the difference with a regular criminal, the criminal usually acts for selfish reasons, either because he needs money or moved by hatred, revenge, or any other kind of personal reasons, and there is no hidden aim of creating a psychological counter effect that shakes the victim mind after the act, nor a conveyance of a political or ethnic message: it is just an act, out of mere greed or human cruelty.

關於恐怖主義的定義向來存在許多矛盾和分歧,但如同恐怖主義專家之一Bruce Hoffman在其著作Inside Terrorism中所述,首要之務為分辨恐怖主義、游擊戰、與一般犯罪的差別,前者與後兩者同樣都是透過武力達到特定目標。儘管達到目標的媒介相同(皆為暴力),但理由卻不盡相同。例如,游擊戰是指一定規模的武裝團體,如軍隊般行動,攻擊敵人軍事力量,掠取並掌握領土(即使只有短暫的數小時),並行使某種形式的統治權或對特定的地理區域及人民進行控制行為。然而恐怖主義並不像軍隊般公開運作,普遍不會試圖掠奪或掌控領土,而會謹慎地避免與敵人進行武裝戰鬥,並且極少的對領土或其人民進行任何直接控制或統治行為」。相較於一般犯罪通常是為了私人理由,恐怖主義者採取行動並非基於金錢所需,或者是被憎恨、復仇或其他個人理由所驅使。從不隱藏其目的是為了製造被害者遭受攻擊後的心理反效果,而非為了傳達政治或族群訊息:僅僅是一種純粹出於貪婪或人性殘酷的行為。

There’s no egoistic, self-satisfying purpose in a terrorist: he is an altruist instead. “He believes that he is serving a good cause designed to achieve a greater good for a wider constituency – whether real or imagined – which the terrorist and his organization purport to represent. “[3] With all of these distinctions in mind, we shall now give Bruce Hoffman final definition of terrorism, which has been widely adopted all over the world, namely: “[…] terrorism is the deliberate creation and exploitation of fear through violence or the threat of violence in the pursuit of political change. All terrorist acts involve violence or the threat of violence. Terrorism is specifically designed to have far-reaching psychological effects beyond the immediate victim(s) or object of the terrorist attack. It is meant to instil fear within, and thereby intimidate, a wider `target audience’ that might include a rival ethnic or religious group, an entire country, a national government or political party, or public opinion in general. Terrorism is designed to create power where there is none or to consolidate power where there is very little. Through the publicity generated by their violence, terrorists seek to obtain the leverage, influence and power they otherwise lack to effect political change on either a local or an international scale. [emphasis added]”[4].

但對恐怖份子而言,其所作所為不是為了滿足私慾,而是一種利他主義:「恐怖主義分子相信自己從事的是良善事業,目的是為了讓廣大的人民能夠得到更好的生活和恐怖份子與其組織所聲稱的更大的 (無論是事實或想像)利益」。目前Bruce Hoffman對恐怖主義的最終定義已經被普遍使用:「恐怖主義是經由使用暴力蓄意地製造和利用恐懼,來追求政治上的改變。所有恐怖行動都涉及暴力或暴力威脅。恐怖主義並不只是為了造成傷害,更是為了灌輸恐懼,進而恐嚇更廣泛的『目標群眾』,對象可能包括敵對的族群或宗教團體、整個國家、國家政府、政黨、或是一般大眾。恐怖主義的目的是為了建立和鞏固權力。透過使用暴力達到宣傳的效果,恐怖分子追求的是能得到影響地方或國際政治改變的手段、影響力和權力」。

Other definitions of terrorism given after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, event that tragically signaled a turning point in relevance and depth of the terrorist discourse, can be equally important, such as the one issued by the Council of the European Union on 13th of June 2002, defining it as “an international act that caused damage to government facility, transport infrastructures, etc. thereby endangering human life and so forth.”[7] The US Department of Defense defines terrorism as “the calculated use of unlawful violence to inculcate fear; intended to coerce or to intimidate governments or societies in the pursuit of goals that are generally political, religious, or ideological.”[8] Here we can see three relevant elements underlined, all aimed at instilling terror: violence, intimidation, and fear, and all the definitions generally agree on these undeniable features. Whatever definition we might choose to attain to, is important to remember that any violent attack against a state or its people must be condemned, whatever the reason that triggered it was.

此外,911事件發生後出現的其他關於恐怖主義的定義也同樣重要,例如2002年6月13日歐盟理事會將恐怖主義定義為「一種破壞政府設施和交通等基礎建設,從而危及人命的國際行為」。美國國防部將恐怖主義定義為「計畫性的使用非法暴力來灌輸恐懼,意圖脅迫或恐嚇政府或社會,以達成政治、宗教、和意識形態的目的」。綜上所述,我們可以從中看到三個相關因素:暴力、恐嚇和恐懼,目的都是為了製造恐怖,而且所有的定義大多同意這些不可否認的特性。但無論我們選擇何種定義,重要的是任何一種用來對付國家或其人民的暴力攻擊都必須受到譴責,無論其所持的理由為何。

“One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter” was a phrase by George Seymour (inHarry’s Game, 1975) particularly famous during the de-colonization, and points out the concrete difficulty in comprehensively defining a term as broad and horrendous as terrorism.

「某人眼中的恐怖份子可能是他人心中的自由鬥士」這是Gerald Seymour(Harry’s Game,1975)在去殖民時期中最著名的一句話,同時也指出要對恐怖主義這種既廣泛又可怕的名詞建立一個完整的定義是相當困難的。

2. Pakistan’s dilemma 巴基斯坦的困境

“The creation of the new State has placed a tremendous responsibility on the citizens of Pakistan. It gives them an opportunity to demonstrate to the world how can a nation, containing many elements, live in peace and amity and work for the betterment of all its citizens, irrespective of caste or creed. Our object should be peace within and peace without. We want to live peacefully and maintain cordial and friendly relations with our immediate neighbors and with the world at large. We have no aggressive designs against any one.” Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, speech given on the occasion of the inauguration of the Pakistan Broadcasting Service on 15th August 1947

「建立一個新的國度給予巴基斯坦人民一個巨大的責任。賦予他們向世界證明一個國家如何在內部仍存在許多不同組成分子的情況下生活在平安與和睦之中;且無論種性或信仰,為全體公民的福祉努力。我們的目標是對內與對外的和平。我們希望和平的生活並保持與近鄰甚至是整個世界的和諧與友好關係。我們沒有任何意圖對抗其他國家的野心。」

─巴基斯坦國父真納(Muhammad Ali Jinnah)在巴基斯坦廣播公司(PBC)於1947年8月15日成立時的致詞

This declaration given by Pakistan’s first leader Jinnah almost fifty years ago sounds dramatically tragic nowadays, echoing in the shadow of suicidal attacks and sectarianvendettas in a country torn apart by hatred and despair, and, as D. Byman writes, “[…]probably today’s most active sponsor of terrorism.”[11] The first challenge that Pakistan offers as a country is defining the security threats, and, more specifically, who should define these threats in the first place; in every democratic country is the political leadership, the force that lead that country, to define the security threats to the state and take action against them or try and preempt them, while in non-democratic ones the military forces are the ones that shape security. As the director of IPCS states, “Pakistan is unique; despite being a democratic government, neither the Parliament nor the government have a complete control over its foreign and domestic policies, including the strategic weapons.”[12] So who detains this control? According to the opinion of the Director of the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, the radical groups and religious parties hold a big share of the political power in Pakistan, and the country’s domestic and foreign policies are largely determined by the so called Establishment; the reason for this is identified in sixty years of weak government and fragile institutions.

巴基斯坦國父真納五十年前的宣言在今天聽來格外悲傷,如今的巴基斯坦已經是一個迴盪在仇恨與絕望的陰影下,且因自殺攻擊與教派仇殺而四分五裂的國家,如同D. Byman寫道「(巴基斯坦)或許是當今恐怖主義贊助者最活躍的地方」。巴基斯坦首先面臨的挑戰就是定義安全威脅,更具體的說,誰來定義這些威脅?對一般的民主國家來說,政治領導者是領導國家的力量,能夠定義國家的安全威脅並採取行動應對或嘗試先發制人;在非民主國家軍事力量塑造安全。正如和平與衝突研究中心(IPCS)主任所述:「巴基斯坦相當獨特;儘管有民主政府,但無論是國會或是政府都無法完全控制國家的外交與國內政策,包括戰略武器。」那麼,究竟是誰在控制? IPCS主任認為激進團體與宗教政黨把持了巴基斯坦大部分的政治權力,國家的國內和外交政策主要由「統治集團」(Establishment)所決定;形塑出巴國建國60年以來軟弱的政府與脆弱的制度。

Pakistan is surely not the only country in the world composed by many different ethnic and religious groups, and yet it stands apart for its unique situation; why is it different then? Manan Amed Asif tried to find a reason for Pakistan’s critique situation and the government’s lack of grip on the society beyond the mere religious discourse, that surely is a relevant framework of analysis, focusing on the rise of the figure of the Prophet as a totalizing narrative after the creation of Pakistan, particularly in Zia ul-haq’s Pakistan, where He became part of every Muslim’s routine and daily political life beyond any expectation. The author argues: “This emergence of the Prophet as a centralising and orienting raison d’etre for Pakistan, however, was not merely an organic outgrowth of a religiously inclined society, it was a deliberate state policy, aided by Islamist parties, to mould public faith. […] With the explicit favor of the military regime, the figure of the Prophet quickly became central to national political memory. […] Within this discourse, the religious right and the Islamist parties, constructed a categorically Sunni Pakistan (implicitly suppressing the Shia veneration of Ali) while projecting a non-sectarian universalism to their public lives.”[15] What Asif argues here is basically that religion is surely an explanation for Pakistan’s fragile political system and total predominance of the Establishment over regular politics, but there are many alternative narratives indeed, and religion alone is not enough.

巴基斯坦肯定不是世界上唯一一個由多族群與宗教團體所組成的國家,但卻呈現出獨樹一幟的情況,為何它與眾不同?Manan Ahmed Asif試圖找出政府為何無法獲取民心的原因,分析先知(穆罕默德)於巴基斯坦建國時所扮演的角色,特別是齊亞‧哈克執政時期,先知已成為穆斯林日常生活與政治的一部分。Asif認為:「先知之所以成為巴基斯坦的核心和存在的理由,不僅是社會篤信宗教下的自然產物;還是經過領導人深思熟慮的國家政策,受到伊斯蘭政黨的援助,為了建立民眾信心…由於軍事政權的喜好,先知的形象迅速成為國家政治記憶的核心…基於上述,宗教正確與伊斯蘭政黨建構起明確的遜尼巴基斯坦(隱含壓抑崇拜阿里的什葉派)、保護大眾生活的非教派普世主義。」從Asif所述可看出,宗教或許可以作為解釋巴基斯坦的政治系統為何如此脆弱以及統治集團能夠完全掌控的原因,但如果只討論宗教便無法完全解釋此一情況。

Other peculiar features might be, religious dimension aside, the control of the State’s power by the Establishment, a Punjabi and Mohair élite now ruled by a federation of the powerful military oligarchy and the élitarian intelligentsia, or the failure of economic growth strategies of any sort, that made the governments, one after the other, more and more dependent on Islam, the abundance of weapons and drugs, especially after the bloody Afghan War (1979 – 1989), and “failure of successive regimes in fulfilling any of their stated developmental agendas [that] led to a basic legitimisation crisis [so that] all regimes, beginning Bhutto’s, began to promote Islam in the affairs of the State. General Zia took this policy further when he began promoting Islamists in the Pakistani Army, which was never done before as it was sought to be a relatively secular institution.”[17]

除了宗教外,其他因素還包括:國家權力被統治集團控制;旁遮普人與穆哈吉爾人菁英透過軍事強人與頂尖知識份子構成的聯盟統治國家;經濟無法成長使得歷屆政府越來越依賴伊斯蘭;1979至1989年的阿富汗戰爭後,武器與毒品的氾濫;歷屆政權無法履行其預定的發展進程導致合法性出現危機。因此從布托以降的各政權開始將國家事務伊斯蘭化,齊亞‧哈克更進一步將伊斯蘭主義推展至過去被認為相對傾向世俗制度的軍隊,這樣的情形前所未見。

The Afghan War (Dec. 1979 – Feb. 1989) and the process of Islamization of the State are considered to be the turning points in the role of Islamic extremism in Pakistan.

1979年12月至1989年2月的阿富汗戰爭與國家伊斯蘭化過程被認為是巴基斯坦國內伊斯蘭極端主義發展的關鍵轉捩點。

3. The Afghan War and its aftermath 阿富汗戰爭及其後果

The Soviet Union intervened in support of the Afghan communist government in its conflict with anticommunist Muslim guerrillas and remained in Afghanistan until mid-February 1989. In April 1978 Afghanistan’s centrist government, headed by President Mohammad Daud Khan, was overthrown by left-wing military officers led by Nur Mohammad Taraki. Power was thereafter shared by two Marxist-Leninist political groups, and the new government, which had little popular support, forged close ties with the Soviet Union, launched ruthless purges of all domestic opposition, and began extensive land and social reforms that were bitterly resented by the devoutly Muslim and largely anticommunist population. Insurgencies arose against the government among both tribal and urban groups, and all of these—known collectively as themujahedeen (Arabic for those who engage in jihad)—were Islamic in orientation.[19] Within Islamic beliefs, the word jihad means not just war but also struggle, strive towards something, and “according to Rajaee (1999), there are two separate ways that jihad is used in the Qur’an. One, a greater jihad, as an internal struggle, based on striving to understand the Qur’an itself or to follow God more closely, and a lesser jihad involving external striving/struggle to remove obstructions to the path of God, which includes struggling against unbelievers.” [20] Pakistan used many mujahedeen groups during the 1970s and 1980s as a part of its own jihad against the Soviet Union, backed up in these operations with massive funds from the United States, United Kingdom, and Gulf countries. As D. Suba Chandran points out, “while the Afghan mujahedeen were leading the jihad against the Soviet troops, the international jihadists assembled for the first time in the region, experimenting with jihad. Osama Bin Laden’s entry into the region was a part of this jihad, along with many Arab fighters, who were ideologically motivated.”[21]

1978年4月,阿富汗由Muhammad Daud Khan領導的溫和派政府被Nur Mohammad Taraki帶領的左派軍官推翻。此後權力由兩個馬列政治團體分享,而缺乏民意支持的新政府與蘇聯建立密切的關係,開始對所有反對派進行殘酷的清洗行動,並進行大規模土地與社會改革,遭到佔人口多數的穆斯林與反共人士所厭惡。對抗政府的動亂由部落和都市發起,這些反抗者被視為聖戰士(Mujahedeen,阿拉伯語意為進行聖戰的人),以伊斯蘭為信念。在伊斯蘭信仰中,聖戰(Jihad)不只有戰爭的意思,也有為某件事情奮鬥、努力的意涵,根據Rajaee(1999):「古蘭經中的聖戰有兩種不同的形式,首先是大聖戰,意指內在的奮鬥,如盡力理解古蘭經、以及更緊密的追隨阿拉;小聖戰涉及外在奮鬥或努力,移除邁向阿拉道路上的障礙,包括對不信者的對抗。」巴基斯坦在1970到80年代利用許多聖戰士團體來對抗蘇聯,並得到美國、英國與海灣國家的大量金援支持。正如D. Suba Chandran指出「當阿富汗聖戰士開始領導這場對抗蘇聯軍隊的聖戰時,也是國際聖戰份子在阿富汗地區的首次聚會、首次經歷聖戰。其中包括賓拉登以及許多受到意識型態驅使的阿拉伯戰士」。

Pakistan trained, paid, equipped, and controlled several mujahedeen groups to have them fight a successful terror war on the Soviets, “[…] Islamabad provided a vast range of assistance to the insurgents, including diplomatic and political support as well as sanctuary, arms, and training. Pakistan exploited the apparatus it had set up in the 1980s to channel support to the anti-Soviet mujahedin in Afghanistan […]”[25], and, as General VN Sharma argues, all of these groups gradually started functioning on their own, just as it happened when the country trained “[…] the tribal groups of the northwest and destitute youth groups on the Punjab province, as a clandestine, ruthless ‘Islamic-jihad Civilian Army’. They were trained […] through the aegis of their secret service, the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI), and the Frontier Corps. They have been used extensively in all Pakistan-India wars and for terrorist operations into Indian territory. […] This policy has given rise to independent and increasingly powerful fundamentalist terrorist organizations. (emphasis added)”.[26]

巴基斯坦訓練、支付、裝備、並控制幾個聖戰士集團,對蘇聯發動一場成功的恐怖戰爭,「伊斯蘭瑪巴德提供叛亂份子眾多支援,包括外交與政治支持,以及庇護、武器、訓練等。巴基斯坦利用1980年代設置的裝備來支持反蘇的阿富汗聖戰士…」如同V. N. Sharma將軍所述,這些團體漸漸開始獨立運作,如同國家訓練他們時所傳授的那樣。「…西北部落團體與旁遮普的貧困青年形成秘密團體『伊斯蘭聖戰平民軍(Islamic-jihad Civilian Army)』…,由巴基斯坦三軍情報局(ISI)與邊境兵團秘密進行訓練。後來這支平民軍被運用在印巴戰爭與對印度恐怖行動…這個政策讓基本教義派恐怖主義團體更加獨立、茁壯」。

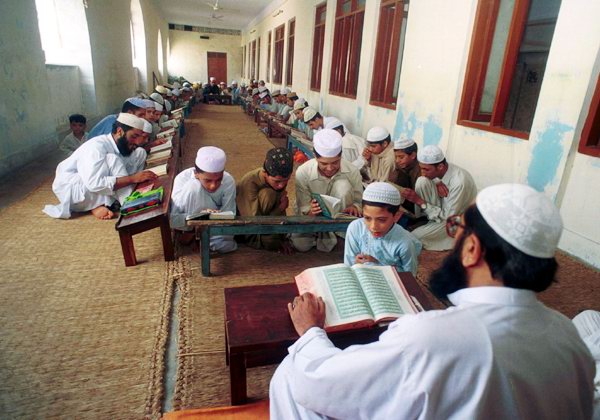

What was the aftermath of the Afghan War in Pakistan? First of all, a massive flow of refugees from the Afghan border, that established in major urban areas such as Karachi increasing tensions and ethnic strives, secondly, among all these refugees were some radical elements, not to consider the mujahedeen trained by Pakistan itself, that entered the country and lead to a sharp shift towards pro-Islamic elements; drug trafficking increased dramatically, and a powerful network of Islamic seminaries, the madrassah, (plural: madaris) established. Madaris were “major source of religious and scientific learning and teaching in Islamic states, especially between 7th and 11th centuries. “[29] These religious schools are currently esteemed to be in a range between 10.000 and 45.000, by 1987 there may have been 3.000, and they were set up to train volunteer students, namely, Taliban, for the war in Afghanistan. Madaris are free, and their growth reflects “[…] a stagnant economy, a collapsed state school system, a desperate situation on the part of many parents, and the dead hand of tradition. […] their growth under Zia was detrimental to both the state and society. Even when not indoctrinated with religious extremism, madrassah students were deficient” [30] in various subjects, and most importantly, they created “a class of religious lumpen proletariat, unemployable and practically uneducated young men who see religious education as a vehicle for social mobility, but who find traditional avenues clogged and modern ones blocked.”[31] Thus, this means that Pakistan lost nearly two generations with this jihadist, often extremist education in the name of terrorism, especially in FATA and NWFP, with substantial numbers having converted to suicide bombers.[32]

阿富汗戰爭結束後對巴基斯帶來什麼樣的影響?首先,大量的難民從阿富汗邊界湧入,導致主要城市如喀拉蚩等地區的緊張情勢與族群衝突上升;其次,難民當中包括部分極端激進分子,不只是受巴基斯坦訓練的聖戰士,使巴基斯坦這個國家更傾向支持伊斯蘭、毒品非法交易更加氾濫,伊斯蘭神學院和宗教學校(madrassah,複數madaris)建立起更緊密的網絡。宗教學校是「伊斯蘭國家學習宗教與科學的主要來源,特別是在第七到十一世紀之間。」巴國境內的宗教學校在1987年只有3,000間,但目前估計已有10,000到45,000間,這些學校成立的目的是為了訓練那些自願參加阿富汗戰爭的學生,也就是塔利班(Taliban)。就讀宗教學校不需付費,這也反映出某些狀況…停滯的經濟發展、崩潰的國家學校制度、家長絕望的處境、以及傳統制度的陰影…齊亞‧哈克時期宗教學校得到充分發展,但這對國家與社會來說都沒有益處。這些學宗教學校的學生即使沒有被灌輸宗教極端主義,但在許多方面仍有缺陷,更重要的是他們建立了一種「宗教無產階級,失業且未受教育的青年將宗教教育視為社會動員的工具,認為傳統與現代的途徑都已遭到阻礙。」這意味著巴基斯坦因為聖戰失去了近兩個世代,特別在聯邦直轄部落地區與西北邊境省,名為恐怖主義的極端主義教育,使很多人選擇成為自殺炸彈客。

Another consequence of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan was, for both Pakistan and the United States, that they both supported extremist groups that were always meant to operate outside both of their countries, the US in particular funded them because they needed a bulwark against Communism, and Pakistan provided them a safe haven in Peshawar and Quetta, [37]but this turned out to be, as we all know, a fatal mistake.

最後,對巴基斯坦與美國而言,兩國都支持極端主義團體,藉以在國外進行工作,特別是美國因為需要對抗共產主義的橋頭堡而資助恐怖主義;巴基斯坦則提供白沙瓦與奎達作為他們的安全天堂。但眾所皆知,這些舉動已犯下致命的錯誤。

4. Forces at work in the Pakistani scenario 巴基斯坦境內的勢力

“Every notion of our independence is nothing but sheer deception and misjudgment. God controls every fibre of our being and none can escape His grip. Not only is our free will and independence delegated by God but the ‘territory’ in which these are exercised is also determined by God and belongs to Him. In this conception, to acknowledge any other entity as being sovereign or to accept any principle of authority is equivalent to idolatry.” –Maulana Mawdudi, founder of the Jama’at-i-Islami, on the concept of divine sovereignty

「任何我們獨立的概念都不過是欺騙與誤解。神控制我們生命且沒有人沒能逃離他的掌控。不只我們的自由意志與獨立是由神所賜予的,所在的「土地」也是屬於神並且由祂決定。在此,承認接受其他的實體自主權或主權原則都等同於偶像崇拜。」

伊斯蘭黨(Jama’at-i-Islami)創始人Maulana Mawdudi,對神權的概念。

As Fredric Grare points out, even though not all Islamists went as far as Mawdudi did regarding divine sovereignty and theocracy, “all concur that the sovereignty of the people is necessarily subordinate to the sovereignty of God.”[1] This contrasts with Pakistan political history, during which many non-state actors and political parties have always strived to exist politically, and the reason for this ambivalence is to be looked for “in the permanent tension between an ideology which considers that sovereignty rests only with God, and the conditions necessary for the emergence and survival of almost all religious political party, namely democracy.”[2]

正如Fredric Grare指出,並非所有的伊斯蘭主義者都支持Mawdudi的神權與神權政治,並且同意「人類主權必然服從於神的主權。」 相反地,巴基斯坦的政治歷史上,許多伊斯蘭非國家行為者與政黨皆致力於從政,這種矛盾產生的原因是來自於「主權源於上帝的意識形態和認為民主是所有宗教政黨的興起與生存的必要條件這兩種觀點之間的衝突是永恆存在的」 。

This tension can be seen nowadays in the lively context of the state and non-state actors that keep proliferating and growing with detrimental effects for the state of health of the governance, that becomes weaker and weaker the more each actor manage to affirm its own existence on the national scene. S. Chandran of IPCS identifies three sets of non-state actors in today’s Pakistan: the first set includes the various factions of the Taliban, like the Quetta Shura, a militant organization of Afghan Taliban. The term ‘Quetta Shura’ originated from Mullah Omar’s relocation of the Taliban organization to Quetta during the winter of 2002, and these people “[…] see themselves as the legitimate government of Afghanistan and aim to extend their control over the entirety of the country. The Quetta Shura Taliban, whose operations have systematically spread from southern Afghanistan to the west and north of the country, is by far the most active enemy group in Afghanistan.”[3]

這種緊張關係至今仍然在國家與非國家行為者之間不斷擴大,並對國家治理造成不利影響,行為者為了在國家舞台上生存反而使國家治理更加弱化。IPCS的S. Chadran將當今巴基斯坦的非國家行為者分成三類:首先是塔利班的各個派別,像是奎達協商會議(Quetta Shura)、阿富汗塔利班的軍事組織。奎達協商會員自2002年冬天Mullah Omar將塔利班組織遷移到奎達,這些成員「…自認是阿富汗的合法政府,並試圖控制整個巴基斯坦。奎達協商會議有系統地將活動範圍從阿富汗南部延伸至西部及北部,是目前阿富汗最活躍的敵對團體」[4]。

Then, there is the Haqqani network, that is apparently under complete control by the Establishment; without it, it could never survive since its territories are quite limited (a few provinces along the Durand Line[5]) and it lacks a strong ideology, not to say the necessary funding, so it is merely a stooge of the Pakistani Establishment.[6]

其次,哈卡尼網絡(Haqqani network)是一個由完全由「統治集團」控制的行為者,活動範圍相當有限,若沒有「統治集團」的支持將無法生存(控制範圍只限於杜蘭德線(Durand Line)[7]周邊部分省份),且缺乏強大的意識形態支撐。哈卡尼網絡可以說是巴基斯坦「統治集團」的一個魁儡[8]。

The third actor in the first set of non-state actors, is the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, also known as TTP: this group is basically an alliance of militant groups in Pakistan formed in 2007 to unify groups fighting against the Pakistani military in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Tehrik-e-Taliban leaders also hope to impose a strict interpretation of Qur‘anic instruction throughout Pakistan and to expel Coalition troops from Afghanistan. TTP maintains close ties to senior al-Qa‘ida leaders, including al-Qa‘ida’s former head of operations in Pakistan. The group has repeatedly threatened to attack the US homeland, and a TTP spokesman claimed responsibility for the failed vehicle bomb attack in Times Square in New York City on 1 May 2010. In June 2011, a spokesman vowed to attack the United States and Europe in revenge for the death of Osama Bin Laden. Islamabad has blamed TTP for most of the terrorist attacks in Pakistan since the group was founded, including the assassination of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto in December 2007. TTP in 2011 claimed responsibility for a number of attacks in Pakistan in the aftermath of Bin Laden’s death.[9] This group is not monolithic in structure, and “[…] it is an umbrella organization deeply divided over tribal lines within the FATA.”[10]

最後,第三個行為者是巴基斯坦塔利班運動(Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan,TTP)。這個團體基本上由巴基斯坦的軍事團體聯盟組成,成立於2007年,當時是為了對抗在聯邦管轄部落地區與開伯爾‧普赫圖赫瓦的巴基斯坦軍隊。TTP領導者希望將嚴格的古蘭經法規落實在巴基斯坦社會,並驅逐在阿富汗駐紮的歐美盟軍。TTP與蓋達(al-Qaida)資深領導人一直維持密切的關係,包括過去蓋達在巴基斯坦行動的領導人。TTP曾多次揚言攻擊美國本土,並宣稱為紐約時代廣場2010年5月失敗的汽車炸彈攻擊負責。2011年6月,TTP發言人誓言要襲擊歐美以報復賓拉登之死。伊斯蘭瑪巴德曾譴責TTP要為巴基斯坦建國後境內發生的絕大多數恐怖攻擊負責,包括2007年12月前總理碧娜芝‧布托(Benazir Bhutto)的暗殺事件。此外,TTP在2011年宣稱為賓拉登死後一系列的攻擊事件負責。[11]這個團體的結構並不嚴密,「如同一個傘狀組織,在聯邦直轄部落地區內不同的部落之間仍相當分歧」[12]。

The second set of non-state actors is composed by India and Kashmir- specific organizations, namely Lashkar-e-Toiba, Jaish-e-Mohammad, and the Hizbul Mujahedeen.

第二類型的非政府行為者是由印度與喀什米爾組成的特殊組織,包括虔誠軍、先知軍和聖戰士黨等。

Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT), often translated as Army of the Righteous or of the Pious, is one of the largest and most proficient of the Kashmir-focused militant groups. LeT formed in the early 1990s as the military wing of Markaz-ud-Dawa-wal-Irshad, a Pakistan-based Islamic fundamentalist missionary organization founded in the 1980s to oppose the Soviets in Afghanistan. Since 1993, LeT has conducted numerous attacks against Indian troops and civilian targets in the disputed Jammu and Kashmir state, as well as several high-profile attacks inside India itself.[13] The LeT’s agenda is outlined in a pamphlet titled “Why are we waging jihad“, and it includes the restoration of Islamic rule over all parts of India and propagates a narrow Islamic fundamentalism. The LeT challenges India’s sovereignty over the State of Jammu and Kashmir and it seeks to bring about a union of all Muslim majority regions in countries that surround Pakistan. “Notwithstanding the government’s declared policy, there is evidence that the Taliban continues to get support in Pakistan today. […] Lashkar-e-Taiba, supported by religious parties and the ISI, continue to operate openly in Pakistan despite Musharraf banning their activities in 2002. So although several Pakistani groups are formally banned, their leaders have not been prosecuted under the Anti-Terrorism Act[14] and these banned entities are allowed to continue operating under new identities with the same leadership.”[15]

虔誠軍(Lashkar-e-Taiba,LeT),意為虔誠或正義之軍,是喀什米爾一帶規模最大且最活躍的武裝團體。虔誠軍在1990年代早期成立,為宣教與指導中心(Markaz ud-Dawa wal-Irshad)旗下的武裝組織,該組織最初成立的目的是為了對抗阿富汗的蘇聯勢力。1993年後,虔誠軍在查謨與克什米爾邦進行多起以印度軍隊與民眾為目標的攻擊行動,並在印度境內發動多起受到矚目的攻擊。[16]虔誠軍在宣傳冊子《為何我們要發動聖戰》中表明,其主要目標包含恢復印度各地伊斯蘭統治以及宣傳狹隘的伊斯蘭原教旨主義。虔誠軍挑戰印度對查謨與喀什米爾的主權,尋求結合巴基斯坦周遭國家以穆斯林為主的地區。「儘管政府沒有表明,但證據顯示時至今日塔利班仍然持續獲得巴基斯坦的支持。…受到宗教團體與三軍情報局支持的虔誠軍,儘管在2002年遭到穆夏拉夫禁止,依舊在巴基斯坦公開運作。儘管一些巴基斯坦團體表面上遭到禁止,他們的領導人並未因為反恐怖主義法(Anti-Terrorism Act)而被追究[17],這些團體的領導者一旦換了新的身分後便被允許繼續運作」[18]。

Jaish-e-Mohammed, meaning Army of Mohammed, is another extremist group based in Pakistan but operating outside the country. Masood Azhar founded the movement in early 2000 upon his release from prison in India, where he was captured during a 1994 mission in Jammu and Kashmir. He remained in prison for several years, but his release was secured in exchange for 155 hostages on an Indian Airlines plane hijacked in December 1999, and he was reported to have received assistance in setting up the JEM from Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, Osama Bin Laden, and several Sunni sectarian outfits based in Pakistan.[19] Soon after his release from jail, Azhar traveled to Afghanistan where he met with Osama Bin Laden. He organized recruitment rallies across Pakistan that called for jihadis to fight in Kashmir, but then he was relegated to house arrest after Musharraf in 2002 froze JEM and its assets; nonetheless, the group kept on operating in some part of the country despite the ban. Their aim is to unite Kashmir with Pakistan and to expel foreign troops from Afghanistan. JEM has openly declared war against the United States, and they have conducted many lethal terrorist attacks, including the bombings of the Indian Parliament in New Delhi in 2001 and of the legislative assembly building of Jammu and Kashmir in Srinagar, October 2001.

先知軍(Jaish-e-Mohammed),意為穆罕默德的軍隊,是另一個以巴基斯坦為基地,在海外運作的極端組織。Masood Azhar在1994年於查謨與喀什米爾活動時被逮捕後,2000年初被印度釋放後成立。他在獄中關了數年,但在1999年12月印度航空飛機遭劫持時以交換155名人質被釋放。報導指出他接受巴基斯坦三軍情報局、阿富汗塔利班政權、賓拉登、以及部分遜尼教派的支持成立先知軍。[20]Azhar出獄後立即前往阿富汗會見賓拉登。他在巴基斯坦四處呼籲聖戰者為喀什米爾而戰,直到2002年穆夏拉夫將他囚禁在家中並凍結先知軍活動與資產,然而先知軍依舊持續在巴基斯坦部分地區活動。他們的目標是將喀什米爾與巴基斯坦合而為一,並將阿富汗內的外國軍隊驅逐出去。先知軍公開表明對抗美國,並且主導多起致命恐怖攻擊,包括2001年德里國會大廈爆炸案,以及同年10月在查謨與喀什米爾首府斯里納加立法機構的爆炸案。

The Hizbul Mujahedeen is a Kashmiri separatist group founded in 1989 by Ahsan Dar, formerly created as the militant wing of Jaamat-el-Islami and allegedly backed up in this process by Pakistan’s ISI (Inter Intelligence Services); the group stands for the integration of J&K with Pakistan and it has also campaigned for the Islamisation of Kashmir.[21] Nonetheless, Suba Chandran defines it a non-state actor on decline, while Lashkar-e-Toiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed has been dismantled or touched at all.

聖戰士黨(Hizbul Mujahedeen)是喀什米爾分離團體,在1989年由Ahsan Dar成立,原本作為伊斯蘭黨(JSI)的旗下武裝組織並受到巴基斯坦三軍情報局支持。聖戰士黨追求將喀什米爾納入巴基斯坦並且也從事喀什米爾地區的伊斯蘭化運動。[22]Suba Chandran認為非政府組織的影響力正在下降,認為虔誠軍、先知軍已經被解散或者被摸透。

The third set of non-state actors is composed by the sectarian forces, mainly belonging to multiple Sunni groups, including Sipah-e-Sahaba (SSP), Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Jaish-e-Mohammad. These cells are largely composed by Punjabi fighters, and are engaged in sectarian vendettas in the FATA[23], particularly in the Khurram and Orakzai agencies.

第三類型非國家行為者由教派力量組成,主要是遜尼教派團體,包括先知之友黨(Sipah-e-Sahaba)、羌城軍(Lashkar-e-Jhangvi)等。這些成員多是旁遮普戰士,在聯邦直轄部落地區從事教派仇殺[24],特別是Khurram跟Orakzai特區。

These Sunni outfits target the minority Shia community of Pakistan, even though Jinnah himself was Shiah and at the élite level there is almost total assimilation among Sunnis and Shias; nevertheless, “on the mass level Shia-Sunni theological differences have always tended to rupture into ugly brawls and violence.”[25] Sectarian violence has always been a part of Pakistan’s history, especially under General Zia-ul-Haq in 1977, when the country’s rhetoric acquired Mawdudi’s quite fundamentalist Sunni overtones,[26] and it was exacerbated by the Gulf region’s power politics, namely in the confrontation between Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran, plus the Iraqi regime’s attempt to cultivate a lobby in Pakistan too; Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia all wanted a role to play in the Pakistani society. “Consequently in the late 1980s large sums of money, leaflets, books, audio and videocassette-tapes poured into Pakistan, projecting one or another point of view. Such propaganda offensive have been backed by the inflow of weapons of a quite sophisticated nature.”[27] This led to the formation of militias such as the above mentioned Sipah-e-Sahaba -devoted to the Companions of the Prophet, a Sunni outfit-[28] a group who wants Pakistan to be declared a Sunni state. Maulana Zia-ul-Qasmi, a leading SSP leader said in an interview in January 1998, “the government gives too much importance to the Shias. They are everywhere, on television, radio, in newspapers and in senior positions. This causes heartburn.”[29] SSP extremists are renown for primarily operating in two ways: either targeting opponent organizations’ activists and kill them, or open terrorist fire on worshippers in mosques of opposing sects.

這些遜尼團體以少數什葉社群為攻擊目標。儘管真納本人是什葉派,在精英階級比例上遜尼與什葉也接近;但「什葉與遜尼的神學分歧導致醜陋的爭吵與暴力。」[30]教派衝突一直以來是巴基斯坦歷史一部分,特別在1977年齊亞‧哈克統治時,國家接納了Mawdudi相當部分的遜尼原教旨主義言論[31];受到海灣地區政治影響,特別是沙烏地阿拉伯(遜尼派)與的伊朗(什葉派)之間的對立;加上伊拉克政權試圖在巴基斯坦建立影響。伊朗、伊拉克與沙烏地都希望在巴基斯坦社會發揮影響力。「1980年代後,大量金錢、傳單、書籍、錄音、與錄影帶湧入巴基斯坦,宣傳一個又一個不同觀點。這些攻擊性的宣傳隨著武器流入國內。」[32]這使得如上述屬於遜尼的先知之友黨等軍事組織紛紛成立,希望巴基斯坦成為遜尼派國家。先知之友黨的領導者Maulana Zia-ul-Qasmi在1998年1月受訪時表示「政府賦予什葉派太多重要性。他們無所不在,不論是電視、廣播、報紙或擔任重要職位。這是妒恨產生的原因。」先知之友黨的極端主義者有兩種廣為人知的攻擊方式:刺殺反對組織領導人或在禮拜時對不同教派的清真寺發動恐怖襲擊。

5. Conclusions 結論

How to reconcile Pakistan’s peculiarly violent context with Musharraf’s repeated assertions that “Pakistan is a true democracy”? More than an assertion, this is probably a wish, because, as Grare underlines, the real question is if democracy in Pakistan have a chance at all; and, looking at its recent history, the future does not seem so bright.

如何將巴基斯坦特殊暴力情況與穆夏拉夫一再強調的「巴基斯坦是真正民主」相互調和?民主對巴基斯坦來說恐怕只是一種願望,如同Grare所強調,即使巴基斯坦的民主仍有一線希望,但觀察巴基斯坦近期的歷史發展,這個國家的未來似乎不太光明。

Yet considering the three elements traditionally blamed for the country’s absence of democracy we might agree that the prospected is not easy by almost structural reasons: instability, Islamism, and lack of development. Anatol Lieven goes even further, assuming that the lack of democracy in Pakistan cannot be blamed entirely on the Army or on the Islamic parties, because the nature of society in Pakistan is lacking democratic superstructures, and “the lack of democratic culture is demonstrated, according to him, by the lack of modern, mass political parties in a country where tradition, loyalty to family, clan, religion, continue to hold sway.”[33]

如果考慮巴基斯坦向來被認為缺乏民主的三個因素,我們或許能同意根本的原因在於國家結構:動盪、伊斯蘭主義、與缺乏發展。Anatol Lieven更進一步假設,巴基斯坦缺乏民主的原因不能完全歸咎於軍隊或伊斯蘭團體,而是因為巴基斯坦的社會本質缺少民主上層建築,以及「缺乏民主文化,Lieven認為巴基斯坦這個國家缺乏現代性、大眾政黨,而對傳統和對家族、宗族和宗教的忠誠仍持續主導該國。」

Therefore, making the country a true democracy and freeing it from the constraints of terrorism will not be an easy process, but, over time, it might become urgently necessary, not just for the international community, but for the country’s population itself.

因此,要讓巴基斯坦成為真正的民主國家並從恐怖主義的限制中解放出來並不簡單,但隨著時間推移,這樣的需求更加迫切,不僅對國際社會而言,更重要的是對巴基斯坦的人民而言。

Bibliography

Ø Ahmed, I. State, Nation and Ethnicity in Contemporary South Asia, London and New York: Pinter Publishers, 1996

Ø Asif, A. Forfeiting the future: Pakistan’s crisis can’t simply be explained by religion,on The Caravan, 2011, available athttp://www.caravanmagazine.in/perspectives/forfeiting-future

Ø Banerji, R. Afghanistan-Pakistan-Iran: Radical Islam, Nuclear Weapons and Regional Security, IPCS Security Brief, No. 191, May 2012

Ø Byman, D. Deadly Connections: States that sponsor terrorism, Cambridge University Press, 2005

Ø Chandran, S. The Crisis state: Pakistan’s security dilemma, IPCS Security Brief, No. 192, May 2012

Ø Cohen, S. The Idea of Pakistan, Brookings Institution Press, 2006

Ø Dressler, J. Forsberg, C. The Quetta Shura Taliban in Southern Afghanistan,Institute for the study of war, Backgrounder, Dec. 21, 2009, available athttp://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/QuettaShuraTaliban_1.pdf

Ø General VN Sharma, PVSM, AVSM (Retd), The Talibanisation of Pakistan, Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. CXXXIX, No. 578, Oct. – Dec. 2009

Ø Grare, F. Does democracy have a chance in Pakistan?, in Pakistan – the struggle within, Pearson Education India, ed. by W. John, 2009

Ø Hoffman, B. Inside Terrorism, Columbia University Press, 1998

Ø Rakisits, C. Pakistan’s Musharraf: playing a balancing act, ASPI Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Insights November 2005

Ø Tadjbakhsh, S. International relations theory and the Islamic worldview, in Non-Western International Relations Theory – Perspectives on and beyond Asia, edited by A. Acharya and B. Buzan, Routledge 2010

Ø Walters, C. Defining terrorism in national and international law, p. 5, available at https://www.unodc.org/tldb/bibliography/Biblio_Int_humanitarian_law_Walter_2003.pdf

Websites

Ø Encyclopædia Britannica www.britannica.com

Ø National Consortium for the Study of terrorism and the responses to terrorism, University of Maryland, US Department of state http://www.start.umd.edu/start/

Ø Terrorism research www.terrorism-research.com

Ø USA National Counterterrorism Center www.nctc.gov/

Ø USA Department of State www.state.gov/

Ø South Asia Terrorism Portal www.satp.org

Ø South Asia Watch www.southasiawatch.tw/