(Source)

Saadat Hassan / PhD Scholar School of Politics & International relations Chinese Version

Quaid-i-Azam university, Islamabad Pakistan

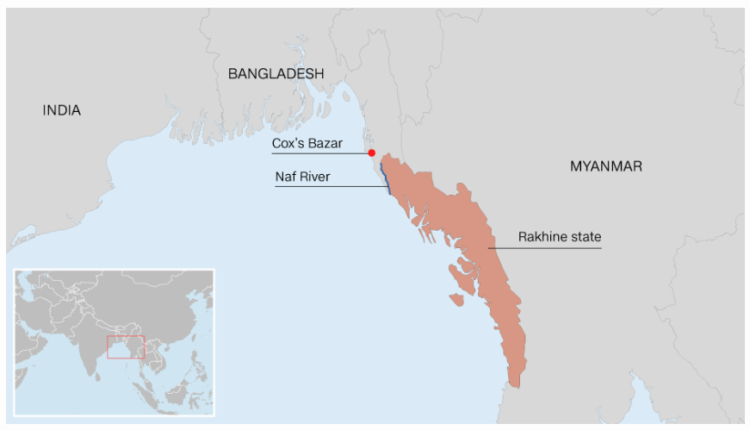

The Rohingyas are minority Muslim groups in a Buddhist-majority land, Myanmar; of the country’s total population of 51 million, only about 1.2 million are Rohingyas, but in the country’s northern Rakhine state, where most Rohingyas live in townships, there are more in number than Buddhists. The United Nations considers the stateless Rohingya to be among the world’s most persecuted minorities.

According to United Nations estimates, about 146,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled from violence in Myanmar since August 25, 2017. The latest surge brings the total number to 233,000 Rohingya who have sought refuge in Bangladesh since October last year, the new arrivals are scattered in different locations in southeastern Bangladesh and More than 30,000 Rohingya are estimated to have sought shelter in the existing refugee camps of Kutupalong and Nayapara; while many others are reported living in makeshift sites and local villages. Nearly five years down the line, this issue is now a full-blown humanitarian crisis and it’s time for the Association of South-East Asian nations (ASEAN) to present a regional response.

- Rohingya Crisis started from 1978

Rohingyas began to flee from military oppression — first in 1978 and then again in 1991-92 — in major influxes of some 500,000 people. Presently, approximately around 32,000 registered refugees stay in the UNHCR-run camps in Cox’s Bazar, while another estimated 500,000 unregistered refugees live outside the camps.

(Cox’s Bazar is at the southern part of Pakistan. Source)

Consequently, most of the unregistered refugees are deemed underprivileged according to the scale of basic human rights and it was seen that by the end of October 2016, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees had registered some 55,000 Rohingyas in Malaysia, most of who had fled by boat. Some 33,000 Rohingyas are living in refugee camps in Kutupalong and Nayapara in Bangladesh; the Bangladeshi government has accommodated the Rohingya to a certain point, but to what extent Bangladesh can support to these Rohingyas considering the fact that Bangladesh itself has limited resources as well as its own population lives under poor conditions, it is really difficult for Bangladesh to manage the sudden pressure which the country has got with the influx of these refugees and it is hardly in a position to resolve the issue on its own.

The Rohingya refugee issue has been a long-standing problem and, unfortunately, the international community has remained mostly mute, unwilling to play a role in helping to resolve the problem. More than 35 years since it began, the Rohingya crisis is long overdue for a solution, the Rohingya crisis is not just an issue for Myanmar; it will impact security and economic trends throughout the region because other countries in an otherwise stable region are becoming embroiled in the crisis; indeed, countries such as Bangladesh, Thailand, and Malaysia are increasingly feeling the spillover effects, as Rohingya seek asylum within their borders. The persecution of the Rohingya can no longer be described as merely a domestic problem for Myanmar.

(Source)

- ASEAN needs to develop a Regional Action Plan

ASEAN was formed in 1967 by five states: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. During 1963‒65, Indonesia had waged war against the formation of the Malaysian Federation, which then included Singapore and ASEAN resulted from an effort to end the war. It was Malaysia who invited Myanmar in ASEAN; Malaysia served as mediator in peace talks between the government of the Philippines and MILF, leading to the 2014 agreement, and Malaysia has tried to help establish talks between the Malay Muslim insurgents in south Thailand and the Thai government, but this was not done under any ASEAN mandate. Myanmar became a member of this regional grouping ASEAN in 1997, contributes to changing the political behavior of its member states.

At this stage the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), it is observed that four of its ten members are directly affected by the crisis: Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Thailand and Malaysia carry a huge responsibility, not only for having tolerated illegal smuggling but also for making use of lowly paid immigrant labor from Myanmar and Bangladesh. As a South Asian country, Bangladesh is not a member of ASEAN but it shares responsibility for the fate of its own out-migrants as well as refugees from Myanmar when they pass through Bangladesh. In view of the recent upsurge of religious conflict in the Middle East, Africa and Europe, it is essential for ASEAN to prevent conflict between Buddhists and Muslims. In the interest of regional peace, ASEAN needs to overcome some of its inhibition against interfering with the internal affairs of its members, and develop a regional action plan to manage and resolve the crisis in the Bay of Bengal.

- ASEAN has been too careful on Rohinya Crisis ?

Refugee management in the ASEAN region is always contentious because refugees are seen as non-traditional security threats and many countries lack effective refugee protection instruments and mechanisms and apart from the Philippines, Timor Leste and Cambodia, no other ASEAN members have signed the Geneva Convention of Refugees and its protocols.

(Source)

The ASEAN region, of which Myanmar has been a member since 1997, is interconnected by common ethnic and religious identities, culture, economic exchanges and migration; this means that any form of humanitarian crisis and extremism growing in one country is a regional security threat. Though the ASEAN Charter underscores respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, and non-interference in the internal affairs of member states, the grouping has recently started to work on regional humanitarian issues, security promotion, conflict prevention and preventive diplomacy. Some ASEAN countries, such as Indonesia have started breaking from the principle of non-interference to comment on the Rohingyas issue and only a limited number of member states are willing to support Myanmar, and efforts are still largely fragmented, uncoordinated and led by individual countries rather than by the ASEAN community as a whole.

ASEAN should consider of forming a minister-level working group with a mandate to address the refugee tragedy as a trans-national issue of long-standing concern to the whole of Southeast Asia. The working group should include ministers from the main countries involved, including Bangladesh, and representatives of the Muslim, Buddhist and Christian faiths. It will also require a change in perspective in other ASEAN members, many of which see the issue as largely a national security issue, rather than a regional problem; but member countries take a conservative approach because non-intervention is a guiding principle of the 1976 ASEAN charter and it is observed that ASEAN members remain divided on whether the Rohingya issue should be approached from a preventative diplomacy standpoint.

ASEAN has been criticized for approaching the Rohingya issue too cautiously, and for failing to recognize that the ongoing conflict could divide the bloc along ethno-religious lines. The region’s population is 60 percent Muslim, 18 percent Buddhist and 17 percent Christian; continued discrimination against the Rohingya already has become a rallying cry for sympathetic Islamic extremist groups in countries that provide asylum and this is especially a grave risk for Muslim-majority countries such as Indonesia.

To avoid a worsening refugee crisis, ASEAN members must move forward with preventive diplomacy and push the Myanmar government to stop political violence in Rakhine state while emphasizing local solutions such as legal and structural reforms that might finally allow the Rohingya to call Myanmar home. It is time for ASEAN to heed this call, shifting its mode of operation, so that mature democracies such as Singapore and Malaysia — which rank high in human-development indices — can become responsible global leaders, as Malaysia seems to recognize this. To conclude, if ASEAN doesn’t wakes up now and play an active role in resolving the issue and continues with it callous attitude towards the Rohingyas then this might break up ASEAN.

Saadat Hassan Bilal, PhD Fellow @ SPIR ,Quaid-i-Azam university Islamabad.